I’ve witnessed and taken part in many debates recently about the future of the Arts and Humanities. In a world where finances are tight and there’s a drive to do better with less, while trying to’measure’ the difference that education makes, investing in subjects like music, literature, history, classics and art is made to seem like an indulgence. Meanwhile we are producing ever-more complex information systems for producing ‘big data’ – generating statistics about human activity on a global scale. For example, the effect we are having as a species upon the planet is now measurable. We can measure the exponential growth of geoengineering, the presence of radioactive isotopes and carbon particles in the atmosphere, increasing ocean acidity and ice cap melt, or even in the number of McDonalds restaurants, spreading virally across the globe. Big data tells us we could be entering the Anthropocene – a new historical-geological epoch, and that as never before we need to get wise and organise to live sustainably and thrive in the twenty-first century. But what will motivate us to lobby for political change, as well as adapt our own behaviour? Big data can make us feel powerless and very insignificant in the face of monumental challenges. This needn’t be the case. We have to find ways to engage people in co-creating a new and better future, and in this endeavour the arts and humanities have a very special, indeed critical, role to play. It is partly a question of scale (the particular and specific over the vast and impersonal), partly about the humanitarian values that can and should underpin creativity, and partly about using powerful media to communicate ideas and narratives, while giving people space to draw their own conclusions. One recent example is the 2015 migrant crisis in Europe. Overwhelming statistics alone were not enough to engage citizens in lobbying for political action to alleviate the humanitarian crisis that unfolded on our doorstep. It took a photograph to bring this back to a scale we could understand – the horrific sight of the body of a single child, Aylan Al-Kurdi, being carried from the sea, to change public opinion. There are still desperate scenes at European checkpoints, but the cheap rhetoric of scapegoating ‘economic migrants’ no longer stands.

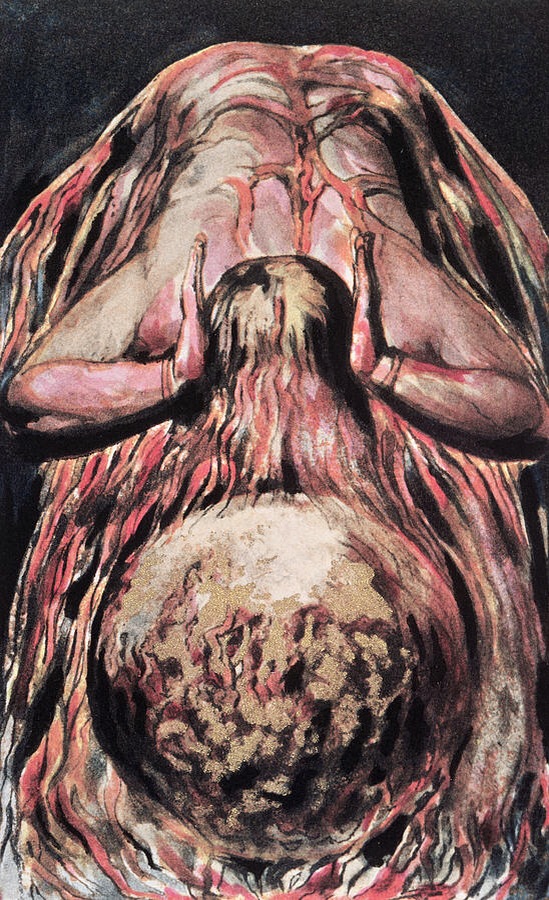

At the recent launch of the Newcastle University Humanities Research Institute, historian David Armitage spoke about the need for deep-time perspectives in order to understand present conditions, and develop future solutions. His book ‘The History Manifesto’ has been misinterpreted as a call for ‘big history’ to supercede microhistory – but my reading is that, like Willliam Blake, Armitage believes it’s possible to see the world in a grain of sand. My view is that the microcosm is not only valid – it’s essential to our ability to grasp and engage with the macrocosm. We need the arts and humanities more than ever.